Getting the ‘what’ and how right of school improvement is fundamental to developing and continually improving schools.

Getting the ‘what’ and how right of school improvement is fundamental to developing and continually improving schools. Schools have priorities to deliver. The ‘what’ possibly to secure an inclusive behaviour system, to build an engaging and rigorous curriculum or to establish excellent teaching from well-qualified, well-trained and motivated staff.

But is a ‘what’ driven strategy the best way to lead improvement or just the received wisdom we perpetuate.

Let’s take a school that wants to develop pupil’s academic language skills. They are research-led and decided what to do based on guidance from the EEF. Their ‘what’ is sound – deliver targeted vocabulary instruction in every subject, provide pupils with a rich oral and written language environment and improve the reading infrastructure. Their ‘how’ involves providing training on explicit vocabulary instruction and support for teachers to understand academic language, prioritising teaching Tier 2 and 3 vocabulary and curriculum planning. The school does improve the use of academic vocabulary in some parts of the school but there is significant and stubborn variation. When you talk to staff, for some the work is transactional – a ‘drop and drag what’ which will be superseded shortly not embedded. Staff have not bought into ‘why’ and focused on outcomes not identity.

“If the teacher makes the weather, the school creates the climate (the ‘why’). School improvement is how schools create an ever-better climate for sustainable impact” (Brighouse, 2015).

So how do you start with the ‘why’ first?

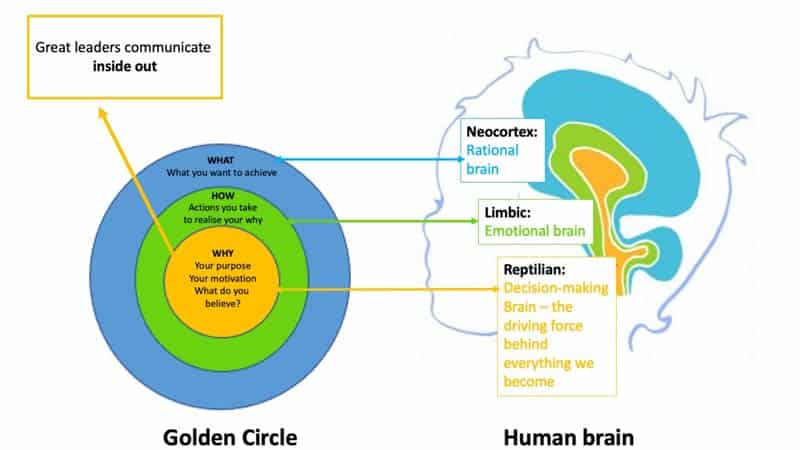

Leadership expert Simon Sinek has a simple but powerful model called the Golden Circle. Instead of putting ‘what’ you do at the core, you start with ‘why’ and work inside out.

He argues successful people and organisations think inside out. I recommend watching his excellent TEDtalk: Start with why – how great leaders inspire action

He explains, if we think, act and communicate from the outside in, we go from the clearest thing to the fuzziest thing. This impairs our ability to make decisions and be effective. Inspired leaders all think, act and communicate from the inside out.

His model Golden Circle exploits knowledge from neuroscience. If you look at a cross-section of the human brain, from the top down, the human brain is actually broken into three major components that correlate perfectly with Sinek’s Golden Circle. Our neocortex corresponds with the “what” level. It is responsible for all of our rational and analytical thought and language. The middle section is our limbic brain, and that’s where all of our feelings, like trust and loyalty derive. Finally, what he terms are reptilian brain responsible for all behaviour, all decision-making; everything we become. So, working from the ‘what’ in doesn’t drive behaviour it is concerned solely with results.

Instead in the schools I work with that think culture and who we want to become they aim for the part of the brain that controls behaviour, and then allowing people to rationalise it with the tangible things we say and do.

‘People do not buy what you do, they buy into why you do it’

Sinek 2019

Perhaps we should be more upfront with ‘why we are doing this’ factor and be unapologetic about returning and returning and returning to it again. After all it is the school’s intrinsic motivation and self-image of who they want to become. In part a simplistic view of accountability is to blame.

The ‘why’ is probably the most important message a school can communicate – it is what inspires others to action.

Currently, securing a ‘why’ is often rushed and surface, confused with vision or assumed to be known ‘… as a teacher at this school we all know why we are doing this… right’.

Talking with new headteachers they all agree the ‘why’ is too easily trumped by the necessity to get the job done. With this new knowledge they all agree this is mistaken and short-sighted.

“When staff are pushing against the limits of time, space, resources, and their own personal limitations – they need to know and recognise the ‘why’.”

“The most important thing we did was investing time in building alignment of staff around the intended school culture creates a shared language, high expectations and coherence … direction and purpose to the staff’s work teaching pupils.”

It doesn’t have to be all about the ‘what’. Schools are creative and passionate places where the lives of children and young people matter. Agreeing the ‘why’ is powerful. The intention is not to trump the important ‘what’, far from it. Keeping the priorities and the shared understanding of the ‘why’ intact will enable us to keep ‘the main thing the main thing’.

In conclusion, understanding the ‘why’ is essential for school improvement, and it sets the stage for deep and sustainable progress. A collective and shared understanding of the ‘why’ can help everyone stay on the same page, collaborate and communicate effectively, and work together as a team towards achieving common priorities.

Fritz writes, when the ‘why’ is “truly shared, we participate in it because we care about it, and we will support it through our participation.”

Knowing the ‘why’ is both an entitlement and necessity. A deep held sense of the ‘why’ creates behavioural coherence across the school and gives direction and purpose to the staff’s work teaching pupils.

As school leaders, it is our responsibility to ensure we know the ‘why’ of our priorities, communicate them effectively, and make collective progress towards.