Time to revise and refine your Pupil Premium Strategy for 2023-24

This is a short blog on updating Pupil Premium strategy documents.

Context

You will need to have updated your Pupil Premium Strategy statement for the 2023/24 academic year by the end of December 2023 and published it on your website. It is a requirement of the conditions of grant to publish an updated strategy statement annually and the DfE will perform monitoring checks on a sample of schools’ published statements. Ofsted inspectors will look at your school’s Pipil Premium Strategy statement on your website to help them prepare for their visit.

You must use the DfE’s template to publish your strategy statement. The template, along with the sample statements to help you fill it out are on the DfE website. The EEF has also published a guide to using pupil premium effectively which complements this document. The DfE template has a five step approach to produce the strategy: 1. Identifying the challenges faced by the school’s disadvantaged pupils; 2. Using evidence to support your strategy; 3. Developing your strategy; 4. Implementing your strategy; and 5. Evaluating and sustaining your strategy.

Actions required

Assuming that you already have a three-year strategy document there is no requirement to produce a brand new document each year rather you should review and renew your strategy annually. As a minimum, note on the template that you are in the second or third year of the strategy and make alterations to any contextual information and premium allocations for this academic year, pupil premium carried forward from previous years and total budget. There may also be some limited changes to Part A: Pupil premium strategy plan as deemed necessary.

What is required annually is the completion of Part B: Review of outcomes in the previous academic year. You must evaluate the progress being made towards achieving the long term strategy success criteria. Often when I start working with a school, I find that they have previously written part B focusing purely on the outcomes of the current year and where these are ‘not good’ are very anxious. However, the DfE intention is to review within the full trajectory of the strategy. Improvement is not always feasible in 12-months but can be in 24-months. It is important to articulate each year as part of the whole. It provides the opportunity for you to recognise a job well-done and to highlight areas that may need more attention. The illustration below shows how useful it is rto eview as part of the 3-year strategy.

| Intended outcome for 2024/25 – the endpoint of the 3-year strategy | Actual 2022/23 |

| The overall absence rate for all pupils being no more than 4% and there will be no gap in attendance for our disadvantaged pupils. The percentage of all pupils who are persistently absent being below 5% and the figure among disadvantaged pupils being no lower than their peers. | Our overall attendance in 2022/23 was lower than in the preceding 4 years at 93.96% and well below the national target of 95% and the schools’ own target of 96%. We have reversed the gap between PP, 93.99%, and NPP, 93.93%, for overall attendance and the gap between PP 16.47% and NPP 16.39% persistent absenteeism has also significantly reduced when compared with the year 21/22. Attendance for all our pupils needs to significantly improve which is why whole school attendance and persistence absenteeism remains a focus of this current plan and features on our school improvement plan for 23-24. |

What if you want to revise more significantly, maybe it’s time to celebrate, calibrate and change?

This can be an exciting opportunity, a way of making the strategy a better fit for your school and ensuring you are utilising the grant and improving the attainment of our disadvantaged pupils in the most effective way for the next 3 years. The Pupil Premium Strategy should be organic, allowing for responses to school developments.

The important thing throughout the change process is to focus on the controllable – the issues that are within the school’s reach.

Seven key points to consider when writing:

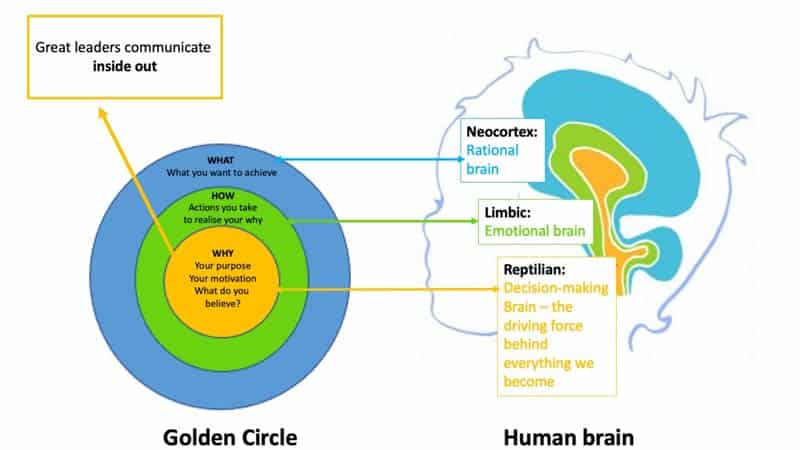

Know your purpose – a plan to reach an objective and not the means of getting there

It is easy to fall into the trap of going too deep and writing an implementation plan rather than a strategy. They go hand-in-hand but there are key differences between the two:

- A Pupil Premium Strategy document offers a top-level overview over the next three years. It will break-down how you are going to achieve your school’s vision or intent statement.

- A Pupil Premium Implementation document on the other hand will outline how you will achieve parts of that strategy. It will include specific actions and active ingredients which will be closely adopted to meet your medium-term objectives and will keep you on track for achieving your long-term strategy. There will be a further blog shortly which tackles effective implementation.

Be honest about capacity

Some schools have taken a ‘kitchen sink’ approach to the number of activities they plan to implement. Their aspirations are unquestionable, but pragmatically such quantity not likely to be as effective. Ask yourself is there:

- sufficient time and resource to monitor and evaluate the number of activities to effectively evaluate their impact; or

- sufficient time in the school’s CPD calendar avoiding shallow CPD or where disadvantage is the tag on.

Think pace and rhythm

You will likely have a range of activities to respond to your challenges. They will be evidence informed. Some will be smaller, quick wins and others will be bigger tasks that require more work and will take longer to embed. Staggering activities will ensure staff are not overwhelmed. Roll-out big initiatives gradually. Schools find this really tricky when improvement is so important to his vulnerable group. But give yourself enough time to implement each new initiative and evaluate. You will get better buy-in and more sustainable impact. People will understand what they are aiming for. A template plan might involve:

- Year one: Choose your new system and run a pilot in one key stage or year group.

- Year two: Review what worked and improve your approach.

- Year three: Roll-out across the school.

- Year four: Review what worked across the whole school and improve your approach.

Write clear objectives and actions

To write-up your plan, you will need to turn your priorities into clear written objectives that give a short overview of what you want to do. Your objectives will need to be quite high-level. You are not trying to write an implementation plan at this stage, so these objectives might still feel quite big, but that is okay, as you will use the latter to break them down further into specific objectives and actions. Make sure the objectives give a clear idea of what you want to achieve and that the targets are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-bound then they can be accountable.

Check the wording

The Pupil Premium Strategy document is a public facing document on your school’s website – fully accessible to all. The wording of the document needs to be cautious and deliberate. For example, it is easy to write the challenges using ‘negative’ language e.g., Poor parental engagement or low aspirations. These are very real challenges that schools face, but they could be re-phrased and still accurate, for example, ‘support parents to engage more positively with learning’. It is important to avoid framing disadvantage as a deficit model. Primarily keep the focus on the learning and ensure efforts to address challenges are focused and precise.

I sometimes find schools using vague success criteria like ‘improve teaching’, ‘improve engagement’ or ‘improve attainment’ because it is the strategy document, and they don’t want to be too operational. The intent is there but strategy doesn’t mean vague. Well defined criteria will be easier to monitor. Consider instead ‘KS2 maths outcomes to show that more than 85% of disadvantaged pupils met the expected standard’.

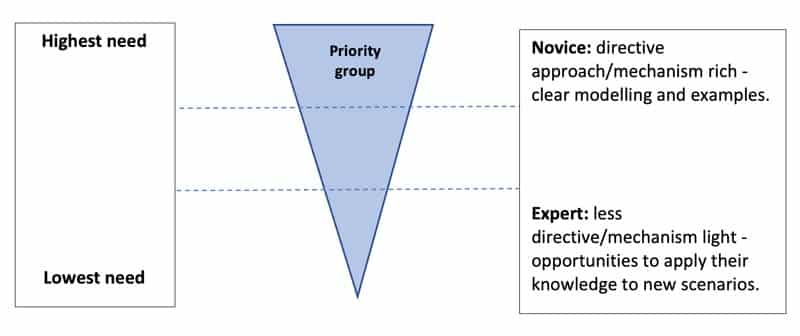

Use assessment not assumptions to agree activities

Poorly identified challenges lead to poorly identified activity, leading to weaker outcomes for pupils and sometimes initiative fatigue. The DfE and EEF’s guidance suggests focussing a greater proportion of activities in high-quality teaching. Providing students access to a high-quality education begins first and foremost with experiencing an effective teacher in every classroom.

The difference between a very effective teacher and a poorly performing teacher is large. For example, during one year with a very effective maths teacher, pupils gain 40% more in their learning than they would with a poorly performing maths teacher. The effects of high-quality teaching are especially significant for pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds: over a school year, these pupils gain 1.5 years’ worth of learning with very effective teachers, compared with 0.5 years with poorly performing teachers. In other words, for poor pupils the difference between a good teacher and a bad teacher is a whole year’s learning. (Sutton Trust, 2011)

Plan the evaluation in to the strategy from the start

Evaluation should be viewed as an ongoing process to support teaching and learning. Marc Rowland talks about using multiple Inadequate glances – looking at learning from multiple angles, and multiple times, before we develop a conclusion and decide on the next steps. When working with schools too often pre and post testing data is used but sometimes this can tell us what we want to see. Similarly writing case studies after the activity ends as proof that it worked is not best practice. Or being overly reliant on the reactions of those delivering the approach.

Four ways we can help you.

1. Conduct a Pupil Premium Review

A pupil premium review looks at how your school is spending its pupil premium funding so that you spend the grant on approaches shown to be effective in improving the achievement of disadvantaged pupils fit for your context.

2. Support leaders to write the Pupil Premium Strategy

Facilitating a strategic writing session enables leaders to work together, supported by an expert, to write their school’s strategy document. The final document will communicate effectively to internal and external stakeholders, including families, advisers and inspectors.

3. Provide strategic support during implementation

We will help you with various aspects of the implementation process, such as moving from strategic to operational planning, creating timelines, identifying active ingredients, monitoring progress, providing training, evaluating results, and adjusting.

4. Plan an expert evaluation

We will support you to put in place a robust evaluation framework at the start of the implementation phase which will enable a rigorous, dispassionate impact evaluation. This will allow you to understand whether strategies are